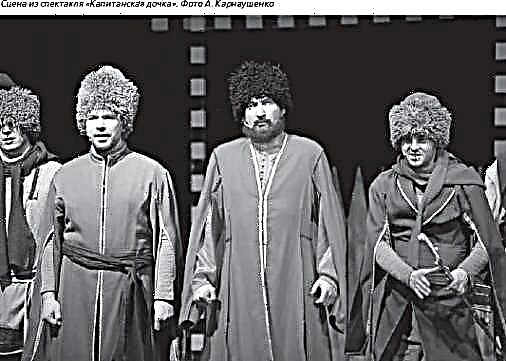

“So Do It in the World” is the last of four comedies written by William Congreve, the most famous of the galaxy of English playwrights of the Restoration era. And although his fame is incomparably greater (both during the author’s life and later), as well as significantly greater stage success and a richer stage history, his other play, “Love for Love”, written five years earlier, was exactly what “They Do the world ”seems to be the most perfect of Congreve’s entire heritage. Not only in its title, but also in the play itself, in its characters is that validity, that detachment to the time of its creation, to the specific circumstances of the life of London at the end of the 17th century. (one of the many fin de siecle in the series, surprisingly similar in many significant ways, most importantly in the human manifestations inherent in them), which gives this play the character of a true classic.

It is this feature that so naturally evokes when reading Kongre's play the most unexpected (or rather, having the most unexpected recipients) parallels and associations. The play “They Do It in the World” is, first of all, a “comedy of morals”, morals of a secular society, which Kongreve knows firsthand. He himself was also quite a secular person, homme du monde, moreover, one of the most influential members of the Kit-Kzt club, where the most brilliant and most famous people of that time gathered: politicians, writers, philosophers. However, by no means they became the heroes of Kongriv’s latest comedy (as, however, of the three previous ones: “The Old Bachelor”, “Double Game” and the already mentioned “Love for Love”), in all of them Kontriv led the cavaliers and ladies who were regulars of secular salons, dandies, empty chimes and evil gossips who know how to weave intrigue at the moment in order to laugh at someone’s sincere feeling or to dishonor in the eyes of the "light" those whose success, talent, or beauty stand out from the crowd, becoming an object of envy and jealousy. All this will develop exactly seventy-seven years later, Richard Sheridan in the now classic School of Slander, and two centuries later, Oscar Wilde in his “immoral morality”: “Fan Lady Windermere”, “Ideal Husband” and others. And the “Russian version”, with all its “Russian specifics” - the immortal “Woe from Wit” - will suddenly prove to be “obliged” to Kongriv. However - Kongrivu? It's just that the thing is that “they act in the light,” and that’s it. Arriving - regardless of time and place of action, from the development of a particular plot. “Are you condemned by light? But what is light? / A crowd of people, sometimes angry, sometimes supportive, / A collection of praises of the undeserved / And just as mocking slander, "wrote seventeen-year-old Lermontov in a poem in memory of his father. And the characteristic that is given in Masquerade, written by the same Lermontov four years later, to Prince Zvezdich Baroness Stral: “You! spineless, immoral, godless, / Proud, evil, but weak man; / The whole century was reflected in you alone, / The present century, brilliant, but insignificant, ”and the whole intrigue woven around Arbenin and Nina,“ an innocent joke ”that turns into a tragedy - all this also fits the formula“ they act in the light ” . And slandered Chatsky - what if not a victim of the “light"? And not without reason, having accepted rather favorably the first of Kongriv’s comedies on the scene, the attitude towards the subsequent ones, as they appeared, became more and more hostile, criticism more and more venomous. In “Dedication” to “Do It in the Light,” Contriv wrote: “This play was a success with the audience contrary to my expectations; for it was only to a small extent assigned to satisfy the tastes which, apparently, dominate the hall today. ” And here is the judgment made by John Dryden, a playwright of the older generation compared to Kongree, warmly related to his fellow worker: “Ladies believe that the playwright portrayed them as whores; gentlemen resented him for showing all their vices, their meanness: under the cover of friendship, they seduce the wives of their friends ... "The letter in the letter is about the play" Double Game ", but in this case, by golly, inconsequentially. The same words could be said about any other comedy by W. Kongriv. Meanwhile, Kontriv just put out a mirror in which he actually “reflected faith”, and this reflection, being accurate, turned out to be very unpleasant ...

There are not many actors in the comedy of Congreve. Mirabell and Mrs. Millament (Contriv calls "Mrs." all of her heroines, equally married ladies and damsels) - our heroes; Mr. and Mrs. Feynell; Whitwood and Petyulent - secular whip and wit; Lady Wishfort is the mother of Mrs. Feynell; Mrs. Marwood - the main "spring of intrigue", in a sense, the prototype of the Wilde Mrs. Chivley from "The Ideal Husband"; Lady Whishforth Fable's maid and Mirabella Waitwell's valet - they also have an important role to play in the action; Whitwood's half-brother, Sir Wilfoot, is an uncouth provincial with monstrous manners, who, however, makes his significant contribution to the final happy ending. To retell a comedy, the plot of which is replete with the most unexpected twists and turns, is obviously a thankless task, therefore we outline only the main lines.

Mirabell, a well-known anemone and irresistible womanizer in all of London, having a staggering success in ladies' society, managed (even outside the play) to turn the head of both the aged (fifty-five years!) Lady Wischfort and the insidious Mrs. Marwood, Now he is passionately in love with the beauty Millament, which clearly reciprocates. But the aforementioned ladies, rejected by Mirabell, are doing everything possible to prevent his happiness from a successful rival. Mirabell is very reminiscent of Lord Goring from “The Ideal Husband”: by nature, a man of the highest degree decent, having quite clear ideas about morality, he nevertheless strives in secular conversation with cynicism and wit not to lag behind the general tone (so as not to pass for a dull or ridiculous sanctuary) and succeeds very much in this, since his wit and paradoxes are not brighter, more spectacular and paradoxical than the rather heavyweight attempts of the inseparable Whitwood and Petyulent, representing a comic pair, like the Gogolevs of Dobchinsky and Bobchinsky (as ..Woodwood .we ... sound like a treble and bass in a chord ... We throw words like two players in a shuttlecock ... ”). The petulant, however, differs from his friend in a tendency to evil gossip, and here the characteristic comes to the rescue, which is issued in “Woe from Wit” to Zagoretsky: “He is a secular man, / An arrogant scammer, a rogue ...”

The beginning of the play is an endless cascade of witticisms, jokes, puns, with each one striving to “recalibrate” the other. However, in this “salon conversation”, under the guise of smiling friendliness, naked disgusts are spoken in person, and behind them - backstage intrigues, hostility, anger ...

Millameng is a real heroine: smart, sophisticated, a hundred goals higher than the rest, captivating and wayward. She has something from Shakespeare's Katarina, and from Moliere's Selimena from The Misanthrope: she finds particular pleasure in torturing Mirabella by constantly tricking and ridiculing him and, I must say, doing this very successfully. And when he tries to be sincere and serious with her, for a moment having removed his clownish mask, Millament becomes frankly boring. She strongly agrees with him in everything, but to teach her, to read morality to her - no, your will, please!

However, to achieve his goal, Mirabell engages in a very ingenious intrigue, the "performers" of which are the servants: Foyble and Waitwell. But his plan, with all its cunning and ingenuity, stumbles upon Mr. Feyndell’s resistance, which, unlike our hero, is known as a modest person, but in reality it is the embodiment of insidiousness and shamelessness, and the insidiousness generated by completely earthly reasons - greed and self-interest. Lady Whishforth is drawn into the intrigue - that’s where the author takes his soul, giving way to his sarcasm: in the description of the blinded confidence in his irresistibility of the aged coquette, blinded to such an extent that her female vanity outweighs all the arguments of the mind, preventing her from recognizing the completely obvious and naked eye cheating.

In general, putting a number of noble ladies and their maids nearby, the playwright clearly makes it clear that, in terms of morality, the morals of both of them are the same — more precisely, the maids are trying to keep up with their mistresses.

The central point of the play is the scene of Mirabella's explanation and Millament. In the “conditions” that they put forward to each other before marriage, for all their inherent desire to preserve their independence, they are surprisingly similar in one: in their unwillingness to be like the many married couples that are their acquaintances: they looked like that “ family happiness ”and they want something completely different for themselves.

Mirabella’s cunning intrigue fails alongside the insidiousness of his “friend” Feynell (“they do this in the light” - these are his words with which he calmly explains - he doesn’t justify, not at all! His actions). However, virtue triumphs in the finale, vice is punished. Some of the heavyness of this “happy end” is obvious - like any other, however, because almost any “happy end” gives a little bit of a fairy tale, always to a greater or lesser extent, but at odds with the logic of reality.

The result is summed up by Mirabell’s words: “Here’s a lesson for those reckless people, / That marriage is defiled by mutual deception: / Let honesty be respected by both sides, / Ile will be searched for a dodger twice”.